Rebooting the Toy Industry

I just got back from New York City’s Toy Fair! While trolling the aisles for inspiring trends towards the future of play, I noticed what’s old is new again, especially in the action figure category. Many of the products are updated releases of vintage properties rebooted for the sake of 80’s nostalgia or to inspire the new generation. Not that I have any problem buying another line of Care Bears for my nieces (or myself)?! I also am a little excited about the Toy Fair announced reboot of Mall Madness, thanks Hasbro!

This got me thinking, we’ve seen a LOT of reboots over the last few decades in movies, TV shows and especially toy properties. Meanwhile, there are a handful of crowd-sourcing independent brands like Creative Beast Studio and The Four Horseman, that are launching totally new properties and doing well on Kickstarter. I think this is so exciting and believe there is a huge missed opportunity for big brands to co-create into new intellectual properties (IP) with indie-brands that are hitting critical mass with their audiences.

This got me thinking, we’ve seen a LOT of reboots over the last few decades in movies, TV shows and especially toy properties. Meanwhile, there are a handful of crowd-sourcing independent brands like Creative Beast Studio and The Four Horseman, that are launching totally new properties and doing well on Kickstarter. I think this is so exciting and believe there is a huge missed opportunity for big brands to co-create into new intellectual properties (IP) with indie-brands that are hitting critical mass with their audiences. Noticing trends across industries, there seems to be a quiet toy renaissance taking place that could have vast potential, much like we saw in the 80’s. It’s happening because toy licensing is becoming less valuable in the same way excessive licensing contributed to the downfall of luxury fashion. A new hybrid business model is emerging from this shift. The most profitable way moving forward will be for larger brands, capable of marketing and scaling quickly, to partner with independent producers.

Noticing trends across industries, there seems to be a quiet toy renaissance taking place that could have vast potential, much like we saw in the 80’s. It’s happening because toy licensing is becoming less valuable in the same way excessive licensing contributed to the downfall of luxury fashion. A new hybrid business model is emerging from this shift. The most profitable way moving forward will be for larger brands, capable of marketing and scaling quickly, to partner with independent producers.

A Brief History of Legalizing Toys in Advertising

In the 1970’s, entertainment properties like Star Wars, Star Trek, Clash of the Titans and the Six Million Dollar Man had catalyzed a shift towards children-based TV programs and the creation of corresponding toy line licenses.

The first toy-led cartoon to air on television was Hot Wheels from 1969-1971. That’s when the Federal Communications Commision (FCC) killed the 30-minute animation’s broadcast under regulations that restricted advertising towards children. In 1974, Strawberry Shortcake was also banned by the FCC. The 70’s and early 80’s were fraught with disagreements on how television programs should be regulated for the benefit of children. Organizations like Action for Children’s Television (ACT), said that it was important for broadcasting to serve children with wholesome, educational programs and considered it “ideological abuse of children” to advertise to them. Of course, Mattel felt that it wasn’t advertising Hot Wheels, it was a cartoon ABOUT Hot Wheels.

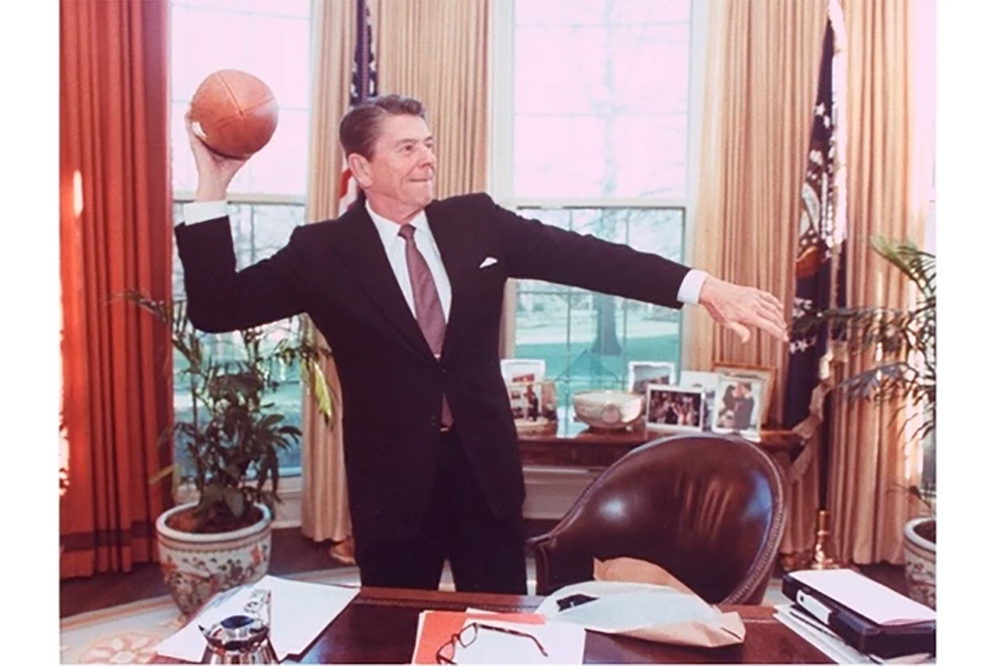

In 1984, the FCC removed regulations restricting advertising towards children until Congress moved to reinstate them a few years later. In 1988, Ronald Reagan put it all to bed when he vetoed the bill as unconstitutional in violation of the First Amendment.

This opened a floodgate opportunity never before seen and created a new market resource where companies could market products using television programs. It was a new, open-ended opportunity to reach children in their homes as a captive audience for hours on end. This created a chain reaction of successful toy lines as Mattel and Hasbro scrambled to compete with Kenner by creating their own IP.

The Intellectual Property Boom of the 80’s

As told in the Netflix series, “The Toys that Made Us,” Barbie was the first big intellectual property developed by a toy company, Mattel. Subsequently, Hasbro developed GI Joe in 1982 as the equivalent boys action figure after failing to acquire the Kenner Star Wars license. In 1984, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe animated series debuted followed by Hasbro’s Transformers, creating a successful new formula. Animated series driven toy properties became a serious game changer. It wasn’t long after, that this pattern of success was recognized by other toy companies and a slew of new in-house development of original intellectual properties quickly became commonplace, often outshining even the most popular licences.

Taking Creative License

What’s currently going on in the toy industry can be read in the same patterns that lead to the downfall of luxury in the fashion industry. In Dana Thomas’s 2007 book, “Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Luster,” Thomas describes how over-extended licensing and distribution tarnished luxury fashion over the course of several decades. Big brands over saturating the market by dividing up licenses with only slight variance to products across categories and vendors. In 2020, luxury brands struggle to gain consumer trust, credibility or interest in a watered down and over supplied marketplace.

Likewise, over the last several decades, toy licenses have been divided up and handed out to multiple companies, leading to a saturation of products with only slight differences and at varying quality. For example, several companies have obtained a license to make Wonder Woman action figures. By dividing the license too many ways, market share and profitability is diluted for all license holders. Even if everyone is buying, no single product is winning market share.

Small is BIG again

One of the major talking points at a Toy Fair panel with Mattel mentioned the company’s collaboration in development labs like The Phluid Project. In this case, the research and development focused around gender fluid dolls for the new line, Creatable World. Mattel’s Head of Global Consumer Insights, Monica Dreger said they often partner with innovation teams and perform qualitative research listening to parents and children during the development of new toy lines. Addressing gender fluidity is a bold move and Mattel is leading the way by collaborating with experts in this space.

In a reversal of this trend, the Jim Henson Company noticed a need for stronger gender diversity for its television series portfolio. In 2017, Jim Henson Co. announced a collaboration with “I Am Elemental,” a 2014 Kickstarter-funded line of action figures aimed at girls.

Larger companies spend a lot of resources on research and development to gather data that often, crowd funded start-ups already have. If bigger companies collaborated with independent developers the incubation process would be more successful because it starts from a passionate talent pool where data and speculation have already been tested.

Kickstart My Heart

President Ronald Reagan’s “freedom of expression” veto opened the floodgates for toy manufacturers to benefit from media entertainment. Similarly, crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter have created freedom of expression for small manufacturers to create new, unlicensed properties.

For big companies, it’s too much of an investment risk to justify unlicensed, essentially untested, IP because there isn’t enough data to project profits and loss. They also don’t have a system for collecting specific data for that audience (unlicensed popularity) because it’s either too broad or doesn’t exist yet.

The reason crowd-sourcing companies are building successful properties is because they are passionately involved in the zeitgeist of toy fandom. These entrepreneurs wholeheartedly believe in the story they are crafting and cultivate an audience through passionate conversation during development.That’s where success has met with the Four Horsemen, Boss Fight Studio, Creative Beast Studio and The Fwoosh. Not to mention the sea of independently developed board games that have later been scaled through big brand buyers. Cards Against Humanity was a Kickstarter launch in 2011. Since then, it’s set off a massive trend of similar card based gaming people just can’t get enough of.

Crowdfunded activity is evidence that the market is ripe for new and unique content because that market is driven by cultivating a culture of fandom. Real people are creating new groups and dynamic market statistics that reveal a new market of opportunity.

Some perfect examples of toy lines ready to scale in a BIG way are:

- Four Horsemen: Mythic Legions

- Boss Fight Studio: Vitruvian H.A.C.K.S

- Creative Beast Studio: Beasts of The Mesozoic

- The Fwoosh: Articulated Icons

Even Tod McFarlane sees opportunities on Kickstarter, at Toy Fair he announced that he plans to relaunch Spawn.

I Wanna Be… BIG

Independent toy makers have an advantage to bring original content to market because they have time and resources to develop slowly, test and improve while building the fan base that would support the product. Big brands can benefit from this process without the investment by cherry picking the ripe and ready developers from crowd-sourcing platforms like Kickstarter. Many of these small developers hit a critical mass of success that they can no longer scale or manage. That’s where big brands can collaborate and profit by partnering with but not acquiring those entities.

With partnerships of larger companies fostering small properties, big brands can scale small markets to shared profitability without taking on the investment risk of R & D or outright buying the company. Larger brands can share in the profit by using their resources to push the content further towards new audiences through media resources such as film, gaming and animation.

While this is a new business model for the toy industry, the model is not new. In the fashion industry, collaborations with independent makers have scored big with consumers. A great example of this is how the Guccighost, graffiti artist known as Trevor ‘Trouble’ Andrew, organically carved a new and exciting direction for the luxury legacy brand that only Gucci itself could have scaled by partnering with the artist in 2016.

The Future is Co-Branded IP

The traditional business model that the larger companies are relying on was built in the late 70’s and original IP making of the 80’s, setting reboot trends that echoed for decades. It’s old hat development with diminishing returns and is ripe for disruption.

Bigger brands would benefit by incubating new ideas outside of their own think tanks and development labs by leveraging crowd-funded platforms like Kickstarter alumni for ready-to-scale properties. If toy companies think outside the traditional licensing model and collaborate with independent producers, profitability and risk mitigation may be negotiable in equal parts. By collaborating through licensing rather than risking resources and investment, a new hybrid business model could reboot the toy industry itself.

Bigger brands would benefit by incubating new ideas outside of their own think tanks and development labs by leveraging crowd-funded platforms like Kickstarter alumni for ready-to-scale properties. If toy companies think outside the traditional licensing model and collaborate with independent producers, profitability and risk mitigation may be negotiable in equal parts. By collaborating through licensing rather than risking resources and investment, a new hybrid business model could reboot the toy industry itself.