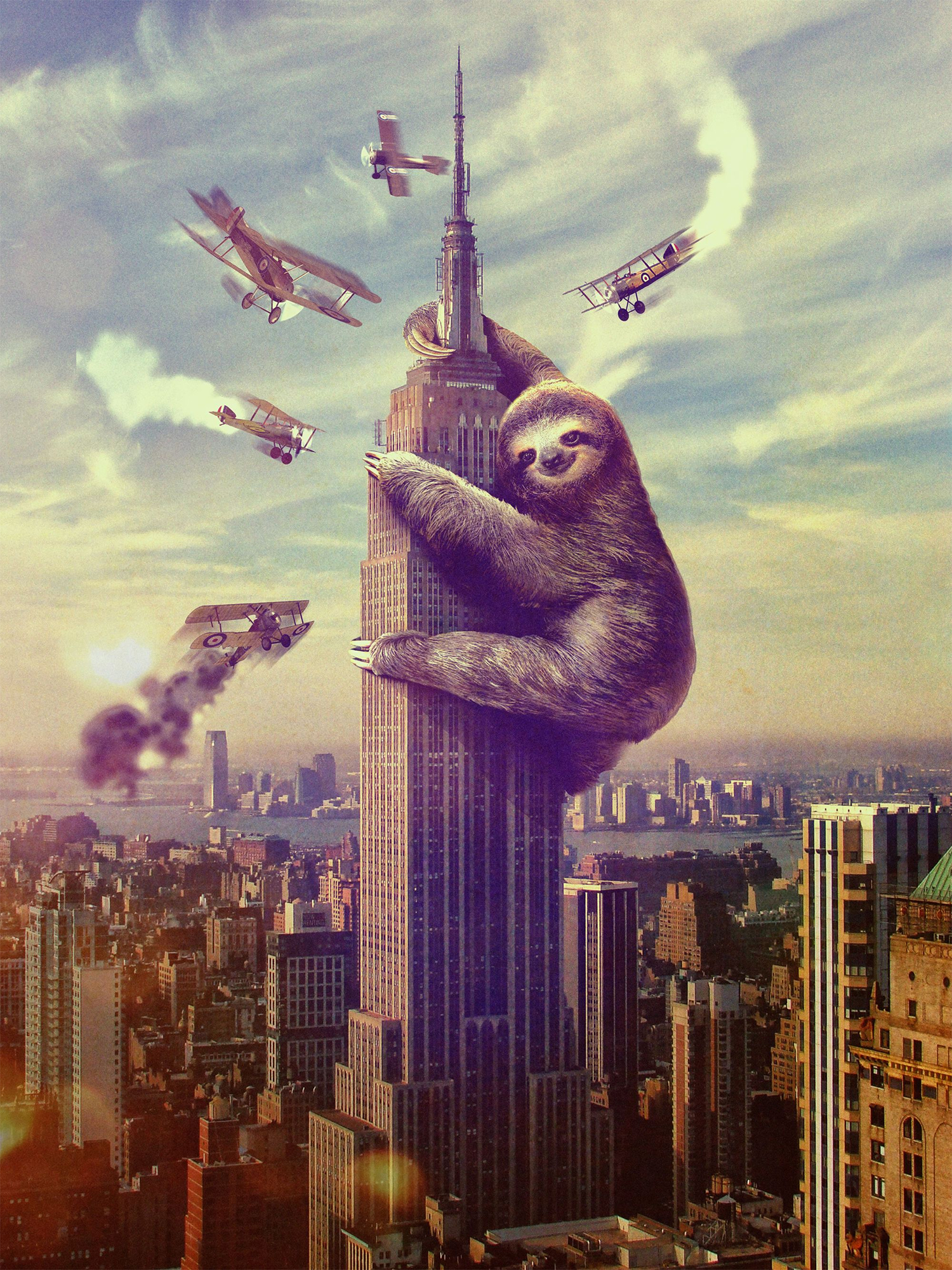

The Sloth: A Model for Urban Design

What does a three-toed sloth have in common with New York City? Well, obviously not speed and agility. Turns out, the three-toed sloth has its own ecosystem that fosters a diverse range of life in it’s fur high above the forest floor. You could say the sloth is similar to a high rise residential building or, almost literally, an eight floor commercial building concept in Nolita. I’m sure you’re thinking that’s a stretch. Allow me to explain.

The Moth and the Sloth

The three-toed sloth is a precarious creature and perhaps inspiration towards building future cities. This particular sloth has it’s very own ecosystem of bacteria and algae that not only is vital to its health but also supports a community of arthropods including moths and beetles. In fact, the entire life cycle of the Cryptoses Choloepi (sloth moth) exclusively relies on the three-toed sloth’s fur for nutrients, a safe breeding ground and eventually laying its eggs in the sloth’s dung on the forest floor to begin the life cycle all over again.

Design by Nature

Climate change, sustainability and public health have become a priority as urban areas are expected to double in population by 2050 according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

In recent months, I’ve visited two fascinating ecology driven exhibitions at the Cooper Hewitt and the MoMA. These museums are bringing to public awareness future facing concepts that combine nature with design. As I write this, NYC museums are closed to the public due to Covid-19 shelter-in-place mandates. While we face a global pandemic, there is increasing opportunity for cross disciplinary designers, engineers and artists looking towards nature to build better cities and better solutions for public and environmental health. No doubt, things are scary, but they can also inspire positive change.

Butterflies in Nolita

So why am I comparing the sloth’s micro-ecozone to an eight story commercial building concept in Nolita? Well, because a relatively new start-up company called Terreform One (Open Network Ecology) noticed how loss of habitat and climate change has jeopardized the Monarch butterfly population which will have dire consequences to our ecosystem and agriculture. During the Nature — Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial exhibition, I got the chance to chat with Co-founder Mitchell Joachim and see the model for myself.

What makes Terreform ONE awesome is their mission to create smart urban innovations that elevate the quality of life in our cities, contribute positively to our ecosystem while reconnecting people with nature. Enter the Monarch Sanctuary, our metaphorical sloth scenario to urban design.

The Monarch Sanctuary will be a new commercial construction integrating a monarch habitat into the facade, roof and atrium. This “vertical meadow” or terrarium will serve as a climate-controlled, all season incubator providing a safe haven of nourishment for all stages of the butterfly’s life-cycle. Providing urban sanctuary to butterflies facilitates the migration patterns necessary to maintain the ecosystem and agriculture that rely on insect populations. Additionally, the terrarium, rooftop and atrium provides bio-active green space for the health and well-being of its human inhabitants. The building will offer a striking example for humans coexisting with diverse life forms in the city while reconnecting urban dwellers with nature. Not at all unlike the Sloth being an essential host to the entire life-cycle of the sloth moth.

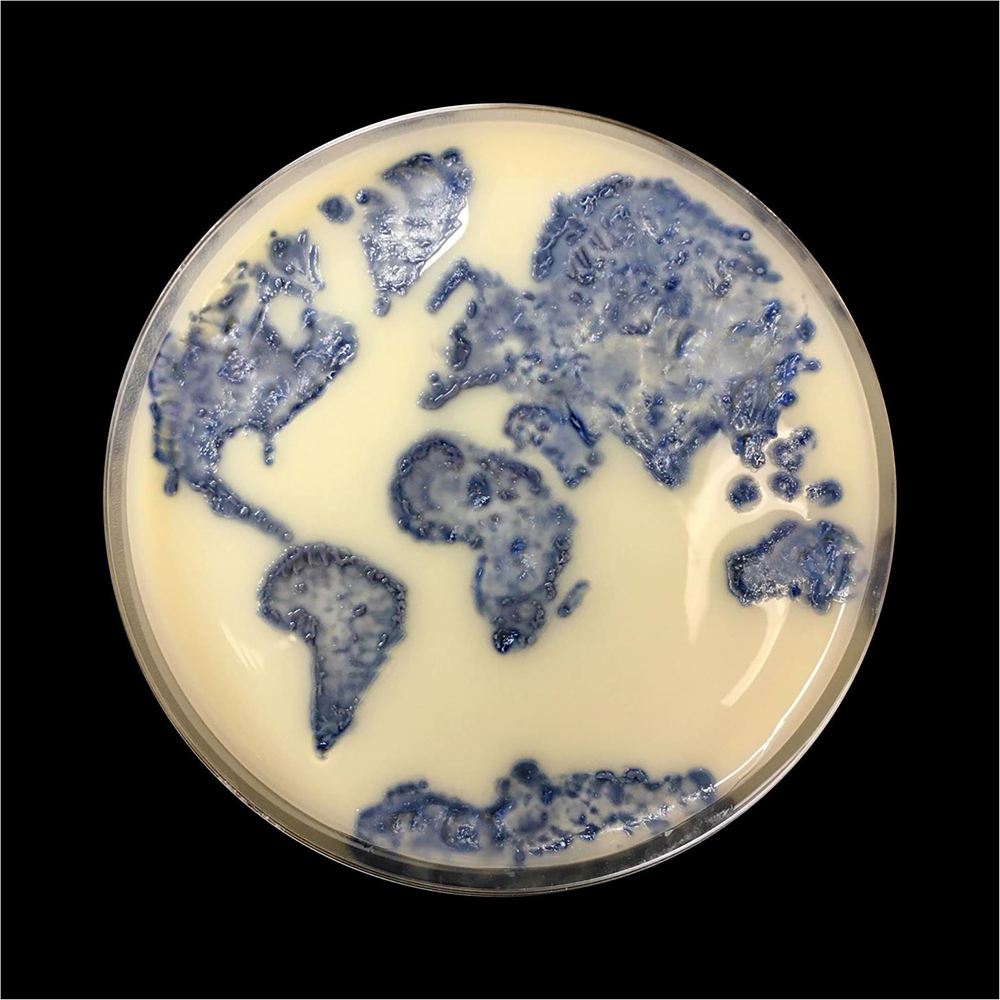

Bacteria and the Built Environment

According to a 2014 study funded by the International Cooperative Biodiversity Group (ICBG-Panama), and the College of Agriculture and Life Science University of Arizona, bacteria from sloth fur could help humans too. The algae and bacteria found on the sloth could be a powerful force against bacterial infections associated with Malaria, among others, and effective against the breast cancer strain MCF-7. Like the sloth, certain forms of bacteria are vitally essential to our health and well-being. Recent studies have shown the absence of healthy gut bacteria in people are linked with depression, anxiety, common food and skin allergies, as well as asthma. Building bacteria back into the environment could be a more sustainable move.

Photo credit SOM © Albert Vecerka Esto

In 2015, architecture firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) designed and built the Bronx Public Safety Answering Center II (NYC’s 9-1-1 call center) with experimental “bio-walls.” For security reasons the building has few windows and thus, limited natural light or view to the outside.

Photo Credit: SOM

For health and wellness purposes the interior’s integrated “bio-walls” contain microbes in the plants’ roots that filter out volatile organic compounds (VOCs), formaldehyde and other toxins in addition to reducing energy consumption while producing oxygen. The bio-walls contribute to the health and well-being of the people inside the facility. Speaking of bacteria in the built environment…

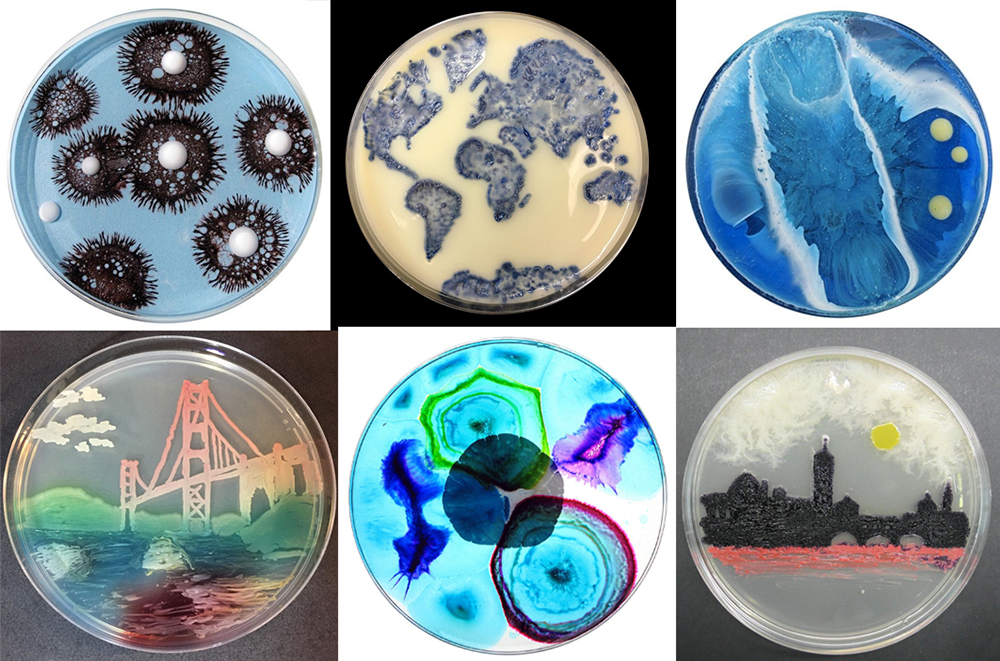

Material Ecology

Neri Oxman is the director at Mediated Matter Group and a professor of media arts and sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab. An innovator at the intersection of biology and technology, Oxman coined the term “material ecology” to describe techniques, objects, materials and construction developed in collaboration with nature, technology and cultural context.

Walking through the “Material Ecology” MoMA exhibition, I was inspired by the idea of growing building materials with bacteria, fungi and melatonin. You can already buy furniture grown from mushrooms. More immediately viable were the Aguahoja I materials created as plastic substitutes printed from biopolymers including cellulose, pectin, calcium carbonate, acetic acid, and vegetable glycerin. The water based materials are designed to decay over time making them perfect prospects for packaging materials and single use consumer products.

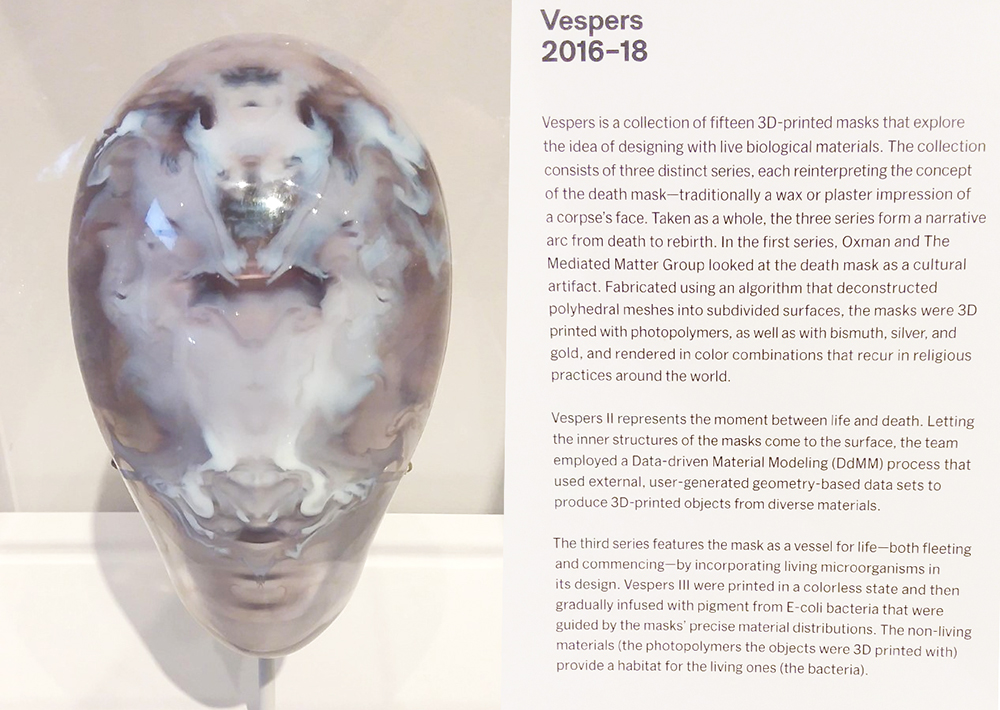

Additionally, the Vespers death masks were infused with natural minerals and bacteria. One even encapsules what would be the deceased’s last breath. Biological design that captures our imagination, immortalizes human frailty and creates solutions to wicked problems such as waste and sustainable materials goes a long way towards inspiring a better future.

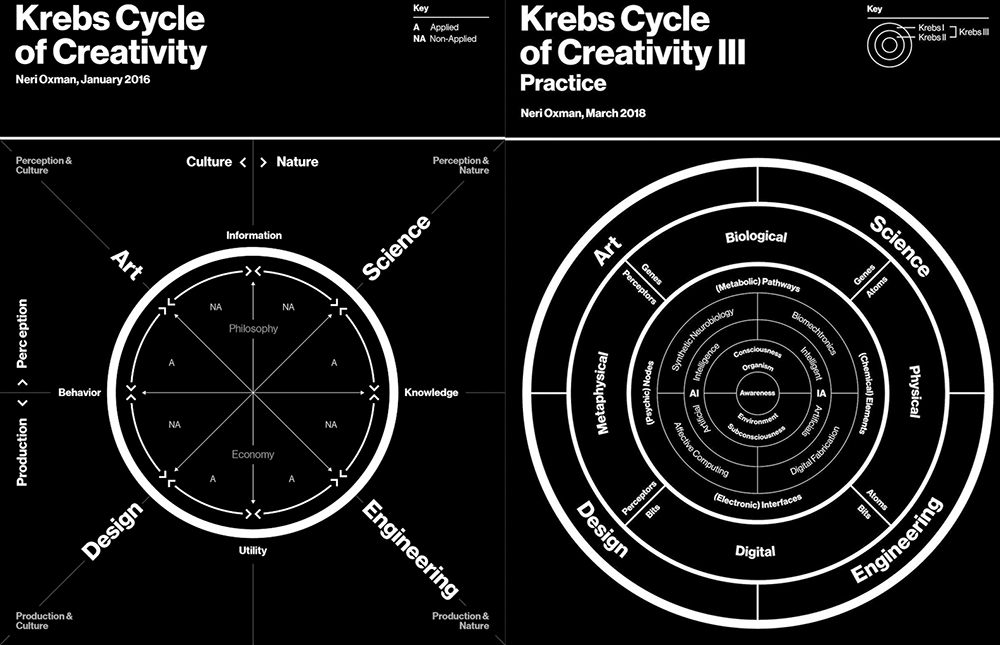

Oxman and her research team operate through a methodological approach called the Krebs Cycle of Creativity. It is a framework that considers art, science, engineering and design as synergistically informing one another. To paraphrase, information is science converted to knowledge, engineering converts that knowledge into utility, design gives utility cultural context and art takes everything into consideration and questions the perceptions of the world. We need greater forms of collaborations, like this, to solve the world’s most wicked problems.

A Call to Action

For the first time in history the entire globe is experiencing a crisis simultaneously. With the spread of Covid-19 coronavirus, the pandemic has also demonstrated the effect we’ve had on the environment. Satellite observation shows China’s air pollution reduced after weeks of shut down and fish return to clearer waters in Venice. Slow reaction and panic have demonstrated how unprepared we are and how little we understand the environment and our impact upon it. It’s time we take an objective, non-political look at what’s happening and call upon scientists, designers and engineers to co-create a better future. It is the role of creative visionaries in art, design, science, technology and business who pull our culture forward into possible futures.